Let me write you letters

5 Oct, 2020

Babe, I want to write you letters. I want to write you letters because it’s a one of the most direct and authentic ways I know of for us to keep in touch, one that can’t be limited by Insta algorithms or caption character counts.

More than that, I want to write you letters because it that feels familiar, like old-skool blogging back when that was still a thing. Like my teenage Livejournal posts read by strangers and friends and strangers that became friends; that hardcoded-HTML flashing-font visual nightmare that nevertheless contained some of the rawest, realest writing I’ve ever shared with the world.

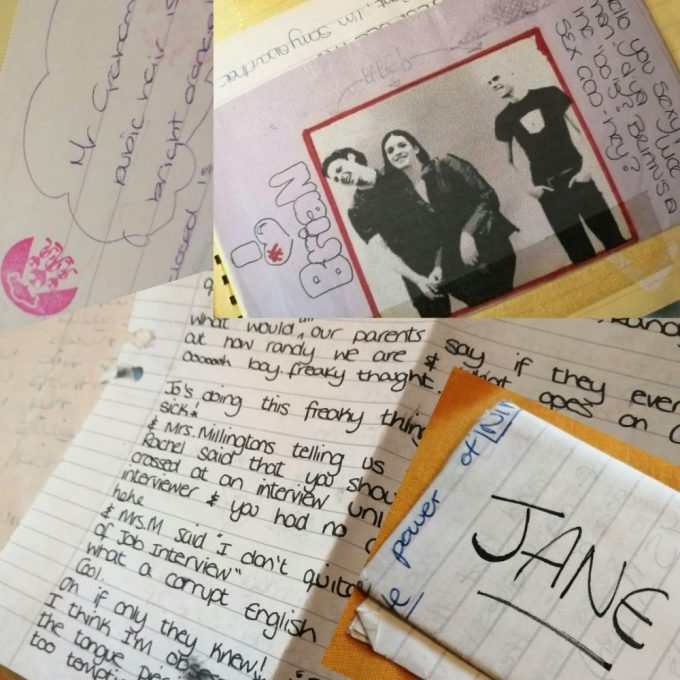

Writing letters reminds me of being at school: when we didn’t have phones to message each other all day long, but we still had way too many thoughts and feelings to possibly go the length of a single lesson without somehow keeping in touch. When we should have been listening to our teachers in R.E or French or Geography, we’d write long letters to each other in the middle pages of our exercise books (all the easier to make it look like we were taking notes, then extract and pass to each other in the corridor next break).

I still have some of those letters, and a lot of their contents are total nonsense (celeb shag lists, speculation about teachers’ sex lives, who copped off with who at that weekend’s parties). But there’s also a lot of real, tender, hard stuff in them: sexual confusion, crushes, clashes with parents, homework stress, heartbreaks and hurts. And tons of creativity: bizarre little illustrations and stories and detailed daydreams (the comic strip of Kurt Cobain, Richey Edwards and Marc Bolan sitting on a cloud in heaven, giving each other manicures and gossiping about the music biz was a particular highlight).

(But I’d still like to think Richey is alive and out there somewhere)

What I didn’t know then about that entire induction into the time-capsule magic of letter writing: it was an unintentional, completely accidental training ground for my immersion into the world of fanzines. When I was fourteen, I found live music, and started going to gigs. On my fifteenth birthday, I persuaded the great-aunt whose annual Christmas present to me was always a magazine subscription that I wanted to switch from Sugar to Rock Sound.

Rock Sound had a penpals page, and I started writing to other kids like me all over the UK. Then one of them sent me a packet full of fanzines: little hand-made magazines talking about the bands I loved that no-one else in my day-to-day had even heard of, and loads of others I’d not encountered yet. That was like getting a secret password to another world I’d never even realised was there: finding out that it had always existed, invisible, alongside mine. Only now I could see it. Now I had a way in. Even better: I had a community. We were geographically distant, but we existed, with a common passion. I was an alienated teenager on a Salford council estate, and this was my lifeline.

By sixteen, my best friend at school and I had started interviewing bands for our own fanzine. We sat in the scruffy backstage rooms of venues and talked to our idols, recording the conversations on our dictaphone to type up later. And that, at the time, was totally magical: the idea that we could share those same spaces with them while they were getting ready, hear them bitch about their hours in the tour bus, share their riders and hear about how they got there; their upbringings and influences and everything else that goes into making music. And working out how to tell those bands’ stories to readers in a way that would make them care did a lot for my writing, and my understanding of writing: its power and responsibility. Even in a tiny photocopied fanzine only ever seen by a handful of readers; friends and strangers and strangers who went on to become friends.

So, all that to say: I believe in letters, and I’m excited to write them to you. If you’ve read this far, thank you. I’ll write to you again soon.

This was part of the first ever edition of my newsletter, which went out to just 29 people back in October 2020.