F🤬ck (your) demons + find community

8 May, 2025

On finding and trusting my voice, coming out, being scared, being safe and being heard…

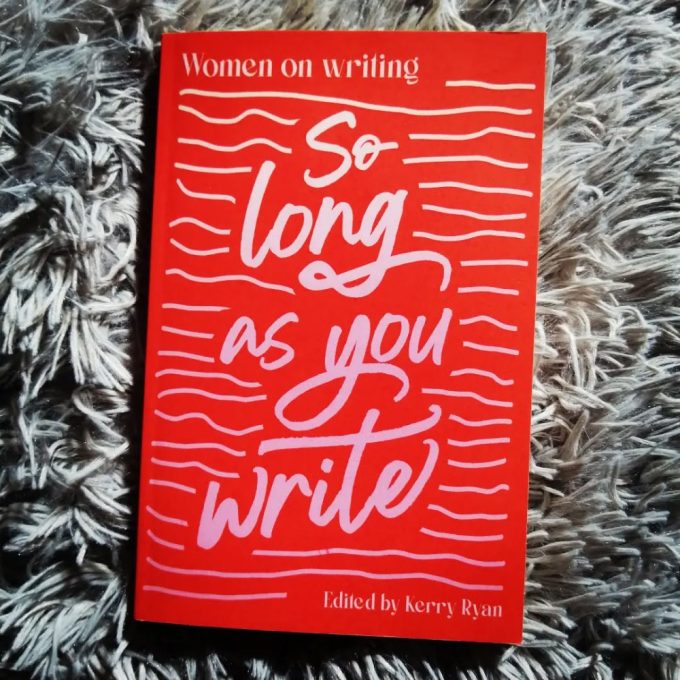

In 2022, I had an essay featured in an anthology called So Long As You Write: Women on Writing, edited by Kerry Ryan and published by Dear Damsels. Last month, Dear Damsels brought an end to their decade-long project and community, meaning that in future it’ll be far harder to find and buy their books. And I didn’t want to lose this piece, so I’m re-sharing it here…

So you’ve found your voice. Or to put it another way: you’ve started to build your trust in that voice you’ve always had. You’ve clawed through the shit to get to the gold, and now you’re starting to believe.

Your writing needs to be shared. It’s an ember glowing inside you, and either you dig it out to use as a lantern-light, or it burns you alive. You find your voice, and then you start to use it. And that’s a thing that, frankly, can be fucking terrifying. Not just nerve-wracking or scary, but a down-to-the-bones beyond-words fear that sends danger, danger warnings storming through body and brain.

So we do what we’ve been taught: we censor and silence and diminish ourselves. Also known as: the most elaborate, invisible, poisonous, cruel and unjust bait-and-switch there’s ever been. Because not being heard can just seem so seductively safe, can’t it? To not risk it, not face our fears, to not put ourselves in a position where we might be met with rejection, criticism, indifference, humiliation. People getting to glimpse our most hidden, secret parts: our dark, weird, messy, rotten, resilient and glorious minds and hearts and souls. Fuck that. Way too exposing. Better to stay quiet, cosy, polite, well-behaved. Slip by unnoticed. Safe.

Except.

Women and marginalised people experience violence every day. And it comes in many slippery forms, from the subtle, insidious and near-invisible to the most brutal and traumatic. It comes from partners, peers, strangers and the systems we live in. We have been and continue to be murdered, tortured and burned alive as witches, for being poor, for living alone, for being healers or widows, for being queer or old or ugly or disabled. Think back over the past few years. How many women’s names are burnt into your consciousness because they were murdered while walking home?

Now tell me: do you still feel safe?

As Audre Lorde wrote: your silence will not protect you. There is only one thing more frightening than speaking your truth and that is not speaking.

Here’s some of how it went for me: A decade ago, I moved back to my home city of Manchester. I’d spent years in Leeds and then London, where I’d slowly found a few keys to the hidden hearts of certain subcultures; secret, pulsing places where everything felt raw and alive and important. Through that process, I discovered parts of myself I didn’t know were there. I fell head-over-arse in love with live performance and spoken word, with queer punk and feminist activism, with squat parties and DIY gigs that come to me now in a swirl of howling guitars, distorted vocals, glitter, sweat and smoke.

During my last year in London, I’d become part of a makeshift feminist arts collective, and started producing events. Until then, I’d strictly stayed part of the audience: intoxicated, energised, envious and terrified. Simultaneously dazzled with admiration and sick with longing to be brave enough to claim those stages as my own. Even when I started putting events on, I never shared my own work. I could create spaces for other people to share theirs, but standing up and reading my own writing? My weird, stilted, perpetually half-abandoned stories that I knew were both too try-hard and too tentative, that just seemed derivative, dishonest and shit? Nah mate.

I moved back to Manchester, on the opposite side of the city to the Salford council estate where I grew up. Maybe now I can become a real writer, I thought. With my living expenses so much lower than in London, I’ll have time to commit to my craft. I researched writing groups, and went to rooms in pubs and libraries and church basements. Passed round print-outs of my work and tried to pretend I wasn’t dying inside at the prospect of having them read.

No-one ever told me how many frogs you have to kiss before you find your prince. No-one ever told me not to take my short story about shagging the devil in a cemetery to the group of lovely middle-class women in their seventies. (One of them loved it, and gave a ton of insightful encouragement, but the other seven stared at me as if I was actually Satan and not just someone who fantasised about fucking demons as a creative pastime.) I persevered for six more months, taking more and more toned-down versions of my work, but I always got told I was too out-there, too unsettling and unpublishable and not using grammar right either.

I stopped going.

There were other groups, but I always came out feeling the same: not good enough, not writing about the right things in the right way, and not even able to do polite writing chit-chat without exposing myself as too loud, too common, too political. And parallel to all of this was me coming out, again, in the city I’d not lived in since my teenage years. Rediscovering the underground queer arts community and all its magic: the music, drag and art. An elevated, more multi-faceted version of that same joyful sense of homecoming I’d found in my earliest adolescent adventures into queer clubbing over a decade before.

I found a queer writing group, for ‘emerging writers’ under thirty. I was six months shy of being too old, and at first I grieved that I’d missed my chance. Then I decided to try my chances and emailed them anyway.

My first meeting, I was buzzed into a dark mouldy corridor beneath a Quaker House. Just follow the music and you’ll find us, a voice instructed me through the crackling intercom. I passed offices with padlocked doors, in the direction of a sleazy sonic beat and muffled voices, finding the chaotic basement headquarters of an indie publisher. No windows, books everywhere: in boxes, on shelves and in precarious towering piles. And there in amongst all this mess:, a cluster of people at the end of a long table wearing an assortment of outfits ranging from bejewelled Indian sari to latex leggings, double denim, afro wig and bowler hat. All of them dancing to a rave track blasting from someone’s laptop.

This was much more like it.

The de-facto leader of this group was a weekend drag queen who had the utmost reverence for the dark arts of performance and theatricality. Part of our responsibility as queer artists is developing and sharing our voices, they said. And that meant literally: if you wanted your writing workshopped, you had to stand up and read it out loud. The first story I shared was about someone being violently assaulted for being queer, then setting fire to a pub with the perpetrators inside. (Had to exorcise my adolescent trauma and pyromaniac tendencies somehow, didn’t I?)

After sharing this story with the group, I sat back down, downed the rest of my tepid tea, waiting for the inevitable soul-crushing that usually followed. And then I got one of the most useful pieces of feedback I’ve ever received. Alright. Good start. Save that version somewhere. Then do a new version of your document. Call that the ‘performance edit.’ Go back to the beginning and strip out everything that isn’t completely necessary.

No one had ever told me anything like that before. And the more I kept going to the meetings, and witnessing all our work evolve, the more I came to understand what should have probably been obvious to me from the start but wasn’t: page and stage are not the same, and if performing is going to be part of how you make yourself heard, they’ll both need developing.

At the end of that first meeting, the group invited me to be in a showcase they were staging in a full-size theatre in just a few weeks time. Jackie Kay was headlining. And I could be part of it too, if I wanted. But I’d have to learn my piece by heart, and perform it rather than read. The workshops and rehearsals that followed were a crash-course in making myself heard, both within the group and with the performance itself.

I’m not saying performance needs to be part of every writer’s practice. And I’m definitely not saying that performing from memory rather than paper should be anyone’s ultimate aim (there are a ton of accessibility issues within that stance, for starters, and I don’t believe in introducing more barriers to an already vulnerable and exposing process). But: it’s something I never expected to be as transformative as it became. I learned how to project my voice. I learned how to use the rhythm, pace and tone of my speech to build momentum, tension and emotion. And I learned a ton about embodiment, about harnessing the adrenaline rocketing round my system and using that as fuel each time I took to the stage to make my performances more hypnotic and exciting.

Even more valuable than these craft elements was that initial advice I received: go back to the start, and strip back. Because within that seemingly simple manifesto was a world of questions I’d never even considered. Which elements were the most important? What was I even trying to say? What did I want to leave the reader or the audience with? And why did that matter? When it was distilled down, to its purest form, why did I want it shared?

For me, this is the crux of being heard, the foundation from which everything else comes. You have to believe that what you have to say is worth sharing. You have to know your why. It doesn’t have to be big or earth-shattering. But it has to matter, to you more than anyone. Whether it’s because you want to rage against the world; share your most secret, precious joys, heartbreaks or shame; connect to a community; highlight injustice; be seen, recognised, accepted and celebrated for who and what you are. To tell a story, be it truth or fiction, and use your actions to advocate for your work. I wrote this, and that matters. I’m here.

For me, being heard was a practice like any other. It took time, energy and courage; it was and is an ongoing process of experimentation, development and refinement. It happened in the most miniscule of increments and in sudden massive shifts. And finding the people to do it with made all the difference. It’s a long, ongoing journey, through sometimes dark and treacherous territory. I couldn’t undertake it alone. Sometimes, the difference between safety and its absence comes down to the company. That writing group had many functions for me, but perhaps the most important was that it brought the fear associated with being heard into a tolerable range. Getting onstage was still scary, but there was also excitement and daft dressing room dances and an underlying unwavering loyalty and pride in each other that mixed in joy alongside the terror and made the latter so much more faceable.

Undeniably, the access to a source of peer mentorship, practice and accountability were incredibly important factors. But it was the mutual understanding, the common language and the trust that came from collaborating with fellow queers for the first time that transformed my confidence. There’s a bell hooks quote that defines queerness ‘not as being about who you are having sex with…but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it, and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and live.’

This was the permission slip I needed, to cast off the shame of continually feeling at odds with the everyday world, and celebrate the pure chaos, beauty and magic you can make when you start revelling in being outside it. Being in a group with drag performers, musicians and artists, all of whom seemed so secure and trusting in their ability and right to be heard despite their writing and art being (sometimes literally) balls-out wild and weird; these were the role models and co-conspirators I hadn’t realised I’d been waiting for.

I was coming to understand my own queerness not just in terms of my sexuality, but as a synonym for alternative, and other. For deviance, defiance, revolution, rebellion and transgression. For subcultures within subcultures and finding validation for all my glorious and furious ideas that had never before had a safe home.

Strip it back to the purest version. Why do you want to be heard?

To make magic, to turn the shit of the past into the strange and harsh and beautiful, and to be witnessed in that. To send up sparks so others can see me. I wrote this, and that matters. I’m here.

We did the show. There were storms that day, but despite the bitter winds and snow outside, we still had a full house. It was my first time performing onstage with professional sound and lighting, on the same bill as luminaries like Jackie Kay and Patience Agbabi. And in the chaos of chatter and celebrating after, one of the group pulled me aside. We’re going to Edinburgh Fringe in August, they said. You’re coming with us, right?

〰️💖〰️

We took the train to Edinburgh together. Our first show, all of us at the venue more than an hour beforehand, fizzy with excitement and anxiety. By this point, I’d been gradually building my performance skills and confidence, but I was still only putting them into action intermittently. This was the first time I’d done any kind of performance more than once. The six of us were sharing rooms, sharing beds in rented-out-for-August halls of residence. We were absolutely spoilt rotten with options for other amazing art to see at Edinburgh Fringe, and we took full advantage, going to numerous things every single day, traipsing for miles back and forth across the city, unintentionally staying out until dawn. But all the while, we did our own shows each day. And in this context, surrounded by other artists at every waking (and sleeping) moment, with thousands of other shows taking place in adjacent rooms at every hour of the day and night, the entire surreal process became bizarrely normalised.

Get up, eat breakfast, go see a gay acapella choir or some punk burlesque, watch a two-person play about intimacy and estrangement in a pub basement, pass a troupe of glam-rock pirates doing David Bowie covers, eat a picnic in an ancient graveyard. Be at the venue in time for your own show. Then more of the same: storytelling and dance performed against a projected backdrop of ethereal animation, erotic acrobatic cabaret, late-night dragged-up poetry and beatboxing. All of which to say: being heard can lead you to some strange and ridiculous places, places you never expected to be.

By our penultimate performance of that Edinburgh Fringe run, I was curled up in a far corner of the pub, napping under my cardigan until ten minutes to show time. At the last one, I was almost late. Over the course of the run, I’d gone from being a wretched ball of pre-performance nerves to almost nonchalant. I’d built trust in myself and the others that I could share my voice and survive the process. That I could tell stories about shagging the devil (because I never gave up on that one, and over time it got edited and remixed into what became my feature monologue in our showcase) by torchlight in a dark room full of strangers, and the world wouldn’t detonate.

Habituation, repeated exposure, the way with enough repetition we adapt to anything. I aged out of the group not long after.

A year later, one of the members invited me to be part of a programme supporting women writers to write for the stage. A year after that, my first full-length play was in production, funded by the Arts Council. I started writing the story that would become my debut novel. A year later, I returned to Edinburgh Fringe, producing and hosting a sell-out run of a spoken word showcase platforming women and non-binary writers. That led to being commissioned to develop and host a year-long series of events at the Royal Albert Hall.

None of it happened smoothly: it involved a shit-ton of self-doubt, stress and late nights sweating over spreadsheets. I relied on other people a lot, and I didn’t do any of it alone. But. And. This is part of what happens: you make yourself heard, you don’t die, and that gives you the fledgling scrap of faith you need to do it again. And you keep building those skills: your craft and confidence and experience. You stretch and realise you’re still alive and then you stretch some more. Your faith builds and starts to get louder than those historic, inherited poisonous whispers that say you’d better not expose yourself, disgrace yourself, show yourself up or let anyone see who you really are inside. You build your courage despite those voices. You are heard, even when everything inside and out is screaming that it’d be safer to be quiet.

There are many things about my identity that make me vulnerable to danger and violence: my gender, my heritage, my sexuality. I am protected and insulated by numerous vectors of privilege, and all these elements co-exist in a complex tangle, as they do for all of us. Am I entirely safe as I navigate the world? No. None of us are. But the act of being heard – however dangerous and vulnerable it sometimes seems – is the thing that keeps me from tumbling into an existential abyss of fear. It is the thing that reminds me of my own small power, the magical thread that keeps me connected, engaged and creating. I do it for me, for the strength and resilience it gives me, and I do it in tribute to that entire artistic ancestral lineage that came before us, to honour their courage and determination to be heard in the face of oppression and adversity. I do it for my community, to renew and re-spell and strengthen the bonds between us. I do it for the writers and artists still battling with everything they’ve got against themselves, their circumstances and their conditioning. I do it for all of us, and the web of protection and solidarity we weave when we advocate for ourselves, our writing and each other.

That ember inside me: I’d rather excavate it and use it as a light to guide me than allow it to burn me alive. That makes me more visible, and with visibility comes risk. But invisibility isn’t safe either. Your silence will not protect you. Silence keeps you hidden: from yourself and from finding or creating the community who might just have everything you need. Sometimes, the difference between safety and its absence comes down to the company. So I’m choosing being heard over hiding. And I hope that you will too, because I want and need your company.

〰️💖〰️

I acknowledge not everyone has the ability to safely use their voice without risking serious harm or even their lives. Re-reading this piece in 2025 hits different than when I wrote it at the bitter end of 2021 (our threat models have changed), but I’m sharing it here the way it was originally published. I feel different about my gender these days too. But the way I feel about queer community still applies, and I still feel that silence can be poisonous and deadly. I still feel that safety can be found and forged through company. And I still enjoy stories about having sex with demons.

Thank you to Kerry for inviting me to be part of So Long As You Write, and to all the Dear Damsels team for the time, thought and work that went into bringing it to life.

Tags: finding your voice, community, performance, writing process, queerness, Dear Damsels